The controversial US military operation in Venezuela has been presented by the US government as a war on drugs, a national security response, and a democracy-restoring mission. But the speed with which the Trump Administration has moved to control oil assets raises more questions than answers: is this less about governance and more about energy dominance? And what does it mean for the energy transition — and, more broadly, for responding to the climate crisis?

Venezuelan oil at a glance

- Total oil seized by US: 35–50 MMbbl

- Daily production (Nov 2025): 952,000 bpd

- Exports to China: 778,000 bpd

- Current WTI price: $56 per bbl

- Current Brent price: $60 per bbl

- Heavy crude type compatible with US refineries

Yesterday, the US government announced it has taken control of between 35 – 50 million barrels (MMbbl) of crude oil, claiming a deal has been reached with the new acting President of Venezuela, Delcy Rodríguez, who was sworn in this week.

At a daily production value of just under 1 million barrels per day (mbd), this is around 1 -2 months’ worth of oil supply at current production levels. At the current oil price, this has a value of around $2.4 billion.

Also yesterday, the US seized two oil tankers, connected to Venezuela, and one of them was sailing under the Russian flag. This prompted an angry response from the Russians, accusing the US of breaking international law.

US government: No oil can leave Venezuela

The US government’s Secretary of State Marco Rubio explained the seizure on the grounds of the sanctions they have placed on the South American country, meaning no oil can leave the country.

Further to this, the government have said that they will continue to control all sales of future Venezuelan oil production.

In an unusual and unprecedented move and claims that will face the test of scrutiny, US Energy Secretary Chris Wright said the US would take the payment for the oil, which he argued would be traded on the international oil market, and give the proceeds to the people of Venezuela.

Is this actually about resource dominance?

Reading between the lines of what has so far been said by Trump’s cabinet ministers, commentators are speculating whether this reflects a more sinister objective in taking control of Venezuela’s oil reserves and assets, to hurt countries not considered allies. This supports the argument that leverage and control may be more important than crude oil quantities themselves.

As the Trump Administration said, they would only allow Venezuela to sell its crude oil if it was in the interest of the US. In other words US will control with whom Venezuela trades.

Vice President JD Vance stated: “We control the energy resources, and we tell the regime you’re allowed to sell the oil so long as you serve America’s national interest, you’re not allowed to sell it if you can’t serve America’s national interest.”

Analysts and commentators speculate that, in the wake of the US-China trade war, given that China is the biggest importer of crude oil from Venezuela, is this actually Trump using Venezuela to wield economic damage on China?

How much crude oil does Venezuela produce?

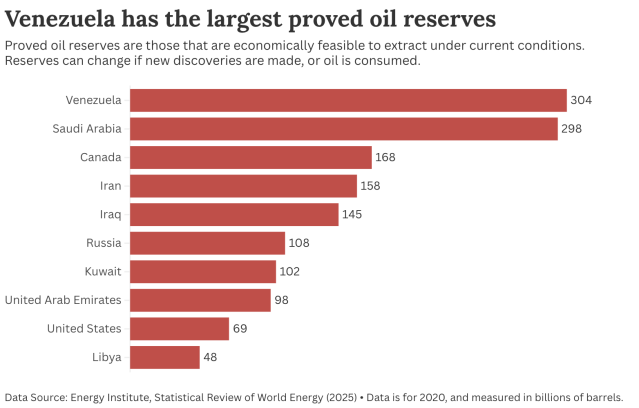

In fact, Venezuela has, even though disputed by some, claimed it has its largest oil reserves in the world, see graph above.

But since it’s crude oil daily production peak of around 3 mbd in the 1980s, it has rapidly declined since then, and per the latest available data as of November 1025, the country produced just 952,000 barrels per day (bpd). Out of this, nearly all was exported to China at 778,000 bpd.

Venezuela production history

- Venezuela production history

- 1980s: Peak production ~3 mbd

- 2000s: Decline begins under underinvestment

- 2025 (Nov): 952,000 bpd

- Current export focus: China (~778,000 bpd)

How much does Venezuelan crude oil actually matter to China?

However, given in context that China is the world’s largest importer of crude oil at around 13.4 mbd, the imports from Venezuela only represent a dent in that and would be unlikely to significantly hurt China economically.

Even though they may have been given a special cut-price deal by Venezuela’s communist government, considering the oil industry was nationalised in 1980, briefly after their production peak under the Hugo Chavez government, China could just increase supply from its largest oil import sources in the Middle East or its ally, Russia.

While Western economies have decreased and are further cutting their gas as well as crude oil imports from Russia, China has no issues with importing from Russia.

The significance, then, is less about how many barrels China loses and more about the US government signalling its willingness to interdict energy flows for geopolitical leverage.

China and Venezuelan oil

- China’s total crude imports: ~13.4 mbd

- Venezuelan share: ~5.8% of total imports

- Heavy crude less suitable for Chinese refineries

- Strategic impact: US can exert leverage, not necessarily disrupt supply

- China can redirect purchases from Middle East or Russia

China is rapidly decreasing its oil demand

Additionally, China is itself a large oil producer and has been increasing production in recent years, and they are making significant progress in reducing its oil demand by electrification – especially in the wake of its rapid adoption of electric mobility. In early 2026, the Chinese electric vehicle (EV) maker BYD even overtook Tesla as the world’s largest EV company.

In the wake of this, it would be plausible to ask, does it really matter to China if it has its Venezuelan oil supply cut off?

How credible are the US government’s promises?

While the US government have said they plan to give the oil revenues to the people of Venezuela, there is as of yet no evidence of this, and the administration has not shared information on the process and whether they will take a cut itself.

Will US oil companies invest in Venezuela?

Trump has said that US oil companies will invest in Venezuela and ramp up production. Though experts have cautioned this and dismissed this as unlikely, and point to comparisons to US military operations in Iraq and Libya and how long it can take to increase oil production. More telling, none of the US oil companies have yet released any public statement confirming that they will invest in Venezuela.

Does the oil price make Venezuelan oil investments feasible?

The other issue is that there are already concerns around oil production oversupply, with pressure on the non-Western oil cartel OPEC to reduce demand.

If production increases, it will push down the oil price, and for oil companies to be convinced about investment in Venezuela, oil analysts say the oil price will need to be a lot higher than it is today, much closer to the $100 mark.

Today, the global crude oil benchmarks, the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent Crude, trade at around $56 per barrel (bbl) and $60 bbl, respectively.

Is the US thirst for Venezuelan oil the real cause for invasion?

Another interesting point worth exploring, and which points to the argument why the US has a significant interest in Venezuela’s oil reserves, is that it fits the type of oil the country needs.

Why can’t US refineries use US crude oil

While the US has surpassed China as the world’s largest oil producer, a lot of the oil they produce is light oil, and the majority of US refineries are designed to treat heavy oil, meaning that they need to export a significant amount of their oil to be treated elsewhere.

But Venezuela’s oil is heavy crude, which would fit US refineries and bring the US closer to energy independence.

Seen through this lens, Venezuelan heavy crude is not incidental, but strategically convenient.

Are the actions by the US legal?

The picture is complex, and we still do not know the full extent of the US’s involvement in Venezuela’s oil industry, or whether gaining control of Venezuelan oil was a central objective of the military operation. Some international law experts have argued that the forcible removal of Nicolás Maduro may constitute an unlawful deprivation of liberty under international law, while others have focused on whether the operation itself violates the UN Charter’s prohibition on the use of force.

Why has Venezuelan oil dominated the discussion in the aftermath of the US intervention?

However, many political commentators and observers find it telling that in the aftermath of entering the country, the majority of the rhetoric from the White House has been around controlling its oil, with the military operation talking points around drugs, national security and democracy having almost magically disappeared overnight.

Even for those talking points, the legal arguments for the military operation have, on their own, been presented as weak by commentators and legal experts

If it comes to light that the main objective of entering Venezuela was control of Venezuela’s oil resources because the country needs it, then the legal argument would enter a whole different perspective and be challenged by lawyers.

Is Greenland next?

All eyes are now on the Danish territory of Greenland, which the US government has repeatedly stated that the US needs to own and control for national security.

They of course also have several oil resources as well as the critical rare earth minerals that the US mainly relies on China for. Last year, China temporarily cut off its rare earth exports as an economic weapon as the China-US trade war escalated between the world’s two largest economies.

Seen in this light, Venezuela may not be an isolated case but part of a broader resource-security doctrine.

Anders Lorenzen is the founding Editor of A greener life, a greener world.

Discover more from A greener life, a greener world

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Analysis, conflicts, Energy, Geopolitics, South America, US, US politics

2 replies »